Report on evaluation and quality assurance process

-INTERACTIVE PRESENTATION-

Leading Organisation

Partner Organisations

The report and particularly this presentation is meant to serve as a source of inspiration for professional teams who, with inspiration from the STEP UP-DC project’s educational output, engage in local projects that are meant to further the CDC-related values and practices (Council of Europe, 2018) in educational settings.

STEP UP-DC project attempts:

- to connect Competences for Democratic Culture (CDC) to Initial Teacher Training (ITT) as well as Continuing Professional Development (CPD),

- to intervene in Practice Training Programmes (PTP) for student teachers and educators (pre-school, primary and secondary education),

- to cover the existing need of introducing the training on CDC,

- to disseminate the CDC training model in the education of the countries of Europe,

- to develop of and implement a Training Program (TP) and its Certification on teaching CDC during the PTP of the student teachers and educators,

- to provide the creation of an Open Educational Sources website,

- to support and disseminate project material/results throughout Europe.

The assessment of the project activities’ quality was organized with a formative intent meaning that preliminary assessment results were, on an ongoing basis, fed back to the planning and implementing project partners, so as to be used in the onward monitoring of project activities.

AGORA was positioned as a semi-external evaluator team, meaning that:

- they took no part in actual decision making, module design work or module implementation within the project,

- from the beginning till the end of the project’s running time, they saw themselves and were seen as genuine project partners.

Thus, they were present as participant observers at partner meetings, they produced and shared evaluators’ notes from these meetings, they engaged in reflective dialogues with the project coordinator and partners, they made efforts to shape an evaluative culture within the project and to make project partners maximally self-evaluative. Briefly put:

They endeavoured to make evaluation useful

The evaluation method used is called impact evaluation (Spehrlich, S & Frölich, M., 2019)

Impact evaluation aims at, not only measuring whether a given intervention reaches its targeted goals, but also whether, or to what extent the means-ends logic on which the intervention is based seems to be valid.

6 Principles of assessment

The chapter presents six intended to ensure that educational assessment activities be “acceptable to learners”. Given that STEP UP-DC has RFCDC as value platform the project follow these principles as a quality yardstick for the project’s assessment activities.

“A valid assessment is one that assesses what it is supposed to assess.” (RFCDC, vol. 3, p. 54) In the project, optimal validity has been assured by these means: The project has RFCDC as its value and practice platform. We are using the RFCDC Competence model (vol. 1, p. 38) which represents this platform in quintessential fashion as basic overall assessment criterion for learner’s self-assessment of the module’s professional learning impact. Further than that, all the module’s Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs) are validated through RFCDC indicators.

“Reliability means that an assessment should produce results that are consistent and stable.” (RFCDC, vol. 3, p. 55) Reliability is endangered if assessment data are collected in contexts where momentary, person-based factors may in important ways put their assessment-irrelevant imprint on the data pool. In the case of STEP UP-DC all assessments done by project staff rely on written, and thus stable, assessment tools.

According to RFCDC (Ibid.) “Equity means that assessment should be fair and should not favour or disadvantage any particular group”. With regard to equity issues in the project, much of the assessment work is not meant to put quality labels on the learners, but to uncover – and thus evaluate – the educational and CDC-related quality of the Training Programme’s teaching material. In such cases equity has no relevance. Yet, two project-internal assessment practices, namely with regard to practicum and certification, do indeed probe into the teacher students’ personal-professional competences at this stage of their journey towards being fully educated teachers. Insofar as assessment procedures are trustworthy and are carried through with due respectfulness (see below), we do not, under these circumstances, see a less-than-favourable assessment feedback as an expression of inequity. Further that, the fact that responses to written questionnaires were kept anonymous may be seen as one more equity-assuring factor.

Transparency is about giving the assessed population “explicit, accurate and clear information about the assessment” (RFCDC. Vol. 3, p. 56). We have paid much attention to this assessment aspect by giving clear, detailed, purpose-explaining instructions, first, at the start of every written assessment tool, then at the start of every new group of questionnaire items. We believe that transparency was helped along by the fact that the assessment-responsible partner, namely AGORA, didn’t work alone in constructing assessment tools. Typically, and based on discussions with Project coordinator and/or partners, AGORA would prepare draft material which would then be further adjusted and improved through partners’ comments and further discussions. Such procedures helped to level out cultural differences between AGORA, located in Denmark and with a professional identity mainly based on organization consultancy, and other partners, located in Greece, Cyprus, UK and Norway, and with a professional identity mainly based on education.

Practicality is about using assessment tools that are “feasible, given the resources, time and practical constraints that apply” (ibid.). We are aware that the questionnaires we asked teacher students to fill in were quite voluminous. Yet, it is also a fact that all persons involved in assessment work are also personally committed and actively engaged stakeholders in the project. Participating teacher students have professional interests in helping the project to succeed in its endeavours. For such reasons we found it legitimate to ask them, within reasonable limits of course, to spend some time doing project-improving assessment work.

RFCDC remarks that (for obvious reasons) the respectfulness principle is “of particular importance in the context of the development of competences for democratic culture” (ibid.). Looking back on the project’s assessment activities, we find no traces of disrespect in the ways we have translated our professional agenda into assessment practice. Conversely, we find that we have shown respect to both teacher students and mentors by, through indirect more than direct means, emphasizing the importance of their contribution to project improvement.

Assessment methodology

Assessment methods included collection of quantitative as well as qualitative data. Quantitative assessment tools (questionnaires) were applied as a means towards securing reliability. Qualitative data, in the form of interviews as well as open questions in questionnaires, were collected as a means towards getting subtle knowledge concerning (hoped for) mindset changes accomplished by the Training Programme – from teacher students as well as student teachers.

Assessment, respondents and assessment tools

Four different stakeholder groups contributed with assessment data:

- By responding to anonymous questionnaires, teacher students in Greece, Cyprus and UK did personal assessments of the experienced need for furthering CDC-based teaching; so-called Needs’ Analysis

- Through oral as well as written responses to interview guides, and based on their pilot testing of Training Programme material, members of the STEP UP-DC project team did personal assessments of 1) the experienced educational value of the Training Programme; 2) their personal-professional gains from having done the pilot testing

- By responding to anonymous questionnaires, teacher students participating in the Training Programme did personal assessments of 1) the Training Programme’s experienced CDC-related learning impact; 2) the educational value of the Training programme’s singular sessions

- By responding to anonymous questionnaires, practicum mentors assessed the teaching performance of STEP UP-DC teacher students as well as their own possible professional gain from having taken part in and contributed to the STEP UP-DC project.

- By responding to anonymous questionnaires, team members responsible for teaching sessions 1-6 of the Training Programme assessed the educational value of workshop activities included in singular sessions.

- Teacher students who have completed the Training Programme may obtain certification by responding to assorted test material assessing their CDC-related learning. These certification activities shall also serve as a pilot test of the online certification procedure placed on the project’s Training Platform.

Assessment data and assessment results

Find here the findings of the data analysis from the assessment activities. They highlight the quality assurance of the project implementation as well as the relationship to the indicators of the quality assurance of the project and, generally speaking, of educational projects such as STEP UP-DC.

Needs’ Analysis aims at investigating the extent to which a nation state’s educational community sees potential value in introducing DC-based teaching programmes. Since Needs’ Analysis points at specific characteristics which may add local attractiveness to a CDC-based Training Programme Needs Analysis also has relevance for Training Programme evaluation.

Data collection tools

Two data collection tools were developed, one interview guide intended for face-to-face interviews (qualitative data), one questionnaire intended for anonymous response (quantitative data);

See here the Guide for oral interview with stakeholders

See here the Written questionnaire for stakeholders and student teachers

Both data collection tools aimed at having respondents do comparisons between 1) the actual state-of-affairs and 2) the ideal, wished-for or optimal state-of-affairs with regard to the occurrence of DC-related teaching in the local educational institutions they knew of. Registered differences between actual / wished-for state-of-affairs could be taken as a quantitative expression of experienced need.

Reflection the relative merits of the two data collection tools:

Oral interview and written questionnaire may both be considered valid ways of collecting data for the Needs Analysis. Oral interview has the advantage of allowing for dialogue between interviewer (who also belongs to the programme’s design team) and interviewee. The interviewer will gain a qualitative, personal understanding of the interviewee’s point of view. Using oral interview may thus enhance formative evaluation objectives at a personal level: add usefulness to the event (Patton 2005). Written questionnaire is much less time consuming to manage. It may be administered on-line. It will give programme designers a more superficial, less ‘interesting’ quantitative information. In this way, choice of written questionnaire implies reduction of formativity. Yet, use of the written questionnaire has the benefit of allowing for comparison between (institutional) stakeholder responses and student responses.

Needs’ analysis results in Greece and Cyprus

In the projects Needs’ Analysis questionnaire results from 360 teacher student respondents from Greece and Cyprus are analyzed. All quantitative responses were provided through 5-point Likert scales. Respondents were first asked to assess …

1. the quality (=depth and clarity) of your understanding of the concept of HRE (Human Rights Education)?

2. the quality (=depth and clarity) of your understanding of the concept of EDE (Education for Democratic Citizenship)?

In the next questionnaire section respondents were asked to do to sorts of reflections on each of the 20 items from the RFCDC Competence model.

3. To what extent do you believe that the following represent appropriate and important learning objectives of formal education in your country?

4. According to you, to what extent does the Teaching Training Programme in your department prepare student teachers to deliver the following learning objectives?

In the final – and optional – questionnaire section was asked, in their own words, to give …

… up to three pieces of important and realistic advice on how a Student Teachers’ Training Programme in your department can prepare future teachers appropriately deliver the above (p. 4) learning objectives and to promote the democratic culture in school education.

With regard to all quantitative data, the Needs’ Analysis report shows detailed statistical data processing. The following findings merit attention:

- Answers to questions 1 and 2 show that roughly 75% of respondents have a less-than-very-good understanding HRE / EDE. From an RFCDC perspective this points at a need for CDC-based training of Greek and Cypriot teacher students.

- Answers to question 3 1) indicate that respondents as a whole are strongly in favour of making RFCDC competences important educational targets; 2) allows for differentiation between the relative importances attached to different competences; 3) Substantial differences are registered between response profiles from the three universities involved. Thus NKUA and UNic show relative similar profiles, whereas the need registered at UoTh is visibly stronger.

- Answers to question 4 indicate that respondents find that their educational institutions provide RFCDC-based teaching at a level far below the wished for level.

With regard to qualitative data (‘up to three pieces of advice’) 143 respondents delivered a total of 312 suggestions. Content analysis of these suggestions led to the forming of five thematic categories:

- Need for more practice and less theory

- Need for education through experiential learning and for experiential learning

- Need for courses related to Democracy in the University program

- Need for intercultural communication and practice in multicultural environments (formal and non-formal education)

- Need for cooperation between students and with a teacher and mentor

Needs’ analysis in UK

The LBU partner found it preferable to investigate RFCDC-related need among professional members of the British educational community. They spent much time and much energy on inviting such members to act as questionnaire respondents, but extremely few showed themselves willing to fill in the questionnaire. By April 2021, LBU partner decided to carry out a much more modest survey directed only at teacher students, and based on the project’s questionnaire with some additions of special interest for their national context. A total of 112 respondents participated.

In discussing their experiences relating to Needs’ Analysis with the STEP UP-DC team, the LBU partner argued that it would be too simplistic simply to regard the described course of events as a failure-to-achieve. Rather, it might be taken as a symptom of presently prevailing professional attitudes among mainstream British educational practitioners and policy makers. An instrumental, job- and market-oriented perspective on education is dominant. Such views are further elaborated on in the IO2 report on certification issues.

Summing up

Investigations in Greece and Cyprus with regard to Needs’ analysis show that Teacher students at partner universities NKUA, UoTh and UNic are strongly in favour of intensifying RFCDC-based training programmes as part of their teacher training activities. Further than that, by showing specific local characteristics, Needs’ Analysis is recommended to future users of the STEP UP-DC programme.

This interview-based assessment was done on two occasions. Main intention behind the two interview sessions was to gather information about:

- the transferability of those Guidelines for designing the Training Program that had been worked out: Were they usable as design tools?

- to get first impressions concerning teachers’ degree of professional satisfaction when working with CDC-based teaching material

First occasion

During Spring semester 2021, two partners, namely UoTh (involving two teachers) and NKUA (involving six teachers) pilot tested a selection of the Training Programme’s teaching material. Online interviews were done with these teachers[1] based on the following five questions.

- Module design work had to follow prescriptions set up by the project. In which ways did you find these prescriptions helpful and/or challenging, cumbersome and/or producing educational value?

- In which ways, if any, did the tested activities differ from your habitual ways of teaching?

- The module designs tested have built on certain expectations concerning students’ ways of responding to specific design components. Were your expectations generally met? – Did interesting surprises occur?

- In case formal assessment was included in the activities tested, please give us your personal assessment of the assessment results. Were results as expected? – Were you positively or negatively surprised?

- Can you point at any specific educational highlights and/or educational problems connected with the pilot tested activities?

Five filled-in questionnaires. Below we do a summary of the most important items of interest as seen from an evaluative perspective:

- All respondents evidently show great enthusiasm for DC-based teaching

- As a group, respondents seem used to an experimental, student-centered, student-activating, and thereby democracy-enhancing teaching style. Probably this fact in part explains their positive reply to project coordinator’s invitation to become part of the Athens group. Yet, STEP UP-DC participation had also provided them with new, but also learning-enhancing professional challenges.

- The Guide, worked out by Project coordinator, for constructing STEP UP-DC sessions was seen as helpful by all respondents. No criticism or ideas for improvement were brought forth.

- The on-line teaching format was, by a number of respondents, mentioned as a challenge – but this challenge stems from Corona conditions, not from the project as such.

- All respondents talk very positively about the quality of students’ outputs and about (generally speaking) students’ enthusiasm.

* One teacher was not interviewed because her pilot testing had not been fully accomplished when the interview was done.

- Among students, some had participated in Project coordinator’s run of session 6, some had not. A number of respondents mention that the former group performed at a visibly higher quality level than the latter group.

- Due to Corona restrictions, students who participated in pilot testing during Spring 2021 were not allowed to do practicum. Interviewees expressed regrets that this important project component had been missing.

- Some interviewees express, when asked, positive sentiments concerning the Athens group’s collaboration style and work atmosphere. These expressions are evidence that the project has not only benefited students’ learning, but also had positive democracy-enhancing effects at an institutional level, cf. Whole School approach. The UoTh partner mentions similar effects.

- One member of the Athens group, apart from expressing professional enthusiasm with regard to her STEP UP-DC experiences, also mentions the risk that the RFCDC-inspired teaching format, if turning out to be successful, may ‘degenerate’ into simply becoming a matter of technique and rule following. It is to be noted that the EWC partner (as manifested at the E1 meeting) has the exact same concerns.

Second occasion

After pilot testing of the full Training Programme (Spring semester 2022), the same group of teachers responded in writing (qualitative data) to a questionnaire where the above five questions were supplemented with questions concerning practical issues (number of students, etc.)

The summary below contains the most important items of interest as seen from an evaluative perspective:

- Similarly to what was the case one year earlier, all interviewees express strong professional satisfaction regarding their participation in the STEP UP-DC.

- Supplementary evidence is conveyed regarding the module’s learning impact on students.

- Some interviewees mention that they see the project as having had a positive learning impact on mentors. This value judgement has, once again, relevance for what RFCDC names Whole school approach.

Summing up

Assessment-wise, university professors actively engaged in module planning and implementation, are definitely not non-biased. They want to experience that the time and energy they have invested in getting acquainted with and implementing CDC-based teaching actually were worth their while. What makes this group’s assessments interesting, however, is not primarily related to the respondents’ judgements concerning the module’s educational merits, but rather to their sincere avowal that, professionally speaking, project participation has been for them an extremely rewarding experience. This avowal we see as one more affirmation of the STEP UP-DC programme’s potentially beneficial impact on educational institutional culture; cf. Whole school approach.

Two sets of assessment tools were applied. One was to register the general CDC-related impact of the entire Training Programme on teacher students. The other asked teacher students to assess the Training Programme’s singular sessions, one by one, with regard to their educational value.

Assessment aimed at registering the general CDC-related impact of the entire Training Programme on teacher students.

Long term assessment of the Training Programme’s CDC-related learning impact on teacher students should be based on the students’ actual capacity to perform in democratic fashion as teachers in ‘normal’ employment. The project doesn’t allow for such an assessment to be made – even if some weak approximation may be had from mentors’ assessment of students’ teaching performance in the practicum context.

Within the project’s given time frame, we found that, apart from practicum assessment, assessment of students’ professional gains should be acquired by registering in what ways, if any, their professional self-image (“I’m a future school teacher”) changed as a result of their project participation. Such a registration should be achieved through a traditional pre- => post-questionnaire,

Assessment procedures

In attachment 5 the post-questionnaire is found. It differs from the pre-questionnaire in that a section on practicum is added. Taken as a whole, the two filled-in questionnaires provide data, both of a quantitative and a qualitative kind.

Learning impact assessment

In this report, we abstain from dealing with the qualitative data. They are meant to uncover possible, and rather subtle changes in respondents’ conceptualization of democracy, citizenship, and the like. These data deserve scrutiny, e.g. in academic articles, but we deem them outside the scope of this report.

Quantitative data are derived from a question catalogue consisting of 39 items, all based on the RFCDC Competence model (vol. 1, p. 38; see figure 1) which represents, in quintessential fashion, the educational value platform on which RFCDC is based. The original Competence model has no more than 20 competence items. Many items, however, contain a large number of sub-competences which would make responding perplexing. We therefore split these items up, thereby arriving at 39 questionnaire items.

Figure 1: The RFCDC Competence model

In the pre- as well as the post-questionnaire, students were introduced to these 39 competence items like this:

Personal assessment of your present competences as teacher of democratic culture

Based on research funded by the European Council, a list of Competences for Democratic Culture has been worked out. These competences are described in the table below. The STEP UP-DC project aims at enabling future teachers to develop and nurture these competences in the children and young people with whom they engage in classrooms and elsewhere. We ask you to go through the 39 listed competences. And, for each of them, indicate the extent to which you see yourself as capable of developing and nurturing the given competence in a classroom setting or elsewhere.

Students responded to items through a five-point Likert scale.

1. Not at all = Light blue

2. Slightly = Green

3. Moderately = Yellow

4. Very much = Red

5. Definitely = Strong blue

All 39 items show upward changes, meaning that respondents as a group see themselves as leaving the module with improved professional CD-competences. In the large majority of cases (roughly speaking 32 items) changes stand out as (in a non-statistical sense) significant. Examples:

- competences in understanding and reflecting on concepts including democracy, freedom, citizenship. Rights and responsibilities; see example below

- Listen, actively, genuinely and attentively to other people’s opinion

Figure 2: Example showing significant change

In seven cases the registered changes are small or moderate; namely the following:

Competences in developing and nurturing capability of pupils to

- Show interest and engagement in public affairs; see example below

- Show flexibility and adaptability in changing conditions

- Adjust attitudes and behaviours according to changing conditions.

- Have linguistic, communicative and plurilingual skills

- Explain one’s own behaviour

- Reflect on my own motives, needs and goals

- Develop of a sense of global citizenship

Figure 3: Example showing small change

It is to be noted, that ‘small or moderate change’ in no way indicates that the respondent lacks the competence in question; but only that he/she doesn’t experience the module as having had a significant impact on the already existing competence.

Teacher students’ assessment of the Training Programme’s singular sessions, one by one, with regard to their educational value.

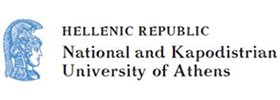

After having completed each of the Training Programme’s sessions 1-6, students were asked to give detailed quantitative assessment of the session in question with regard to its educational value. Two sub-assessments were asked for. One dealt with the session’s Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs) according to the following instruction:

The session you have just completed had N <number – added by teacher> Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs), as listed below. For each ILO we ask you to assess the extent to which the session has succeeded in making you achieve the intended learning outcome.

Below we show graphic representations of two teacher students’ assessments regarding ILOs. One (figure 4) refers to session 1 which activated the least positive assessment results.

Figure 4: Teacher students’ assessment of session 1 with specific regard to ILOs

The next figure (5) shows assessment results from session 4 which activated the most positive assessment results.

Figure 5: Teacher students’ assessment of session 4 with specific regard to ILOs

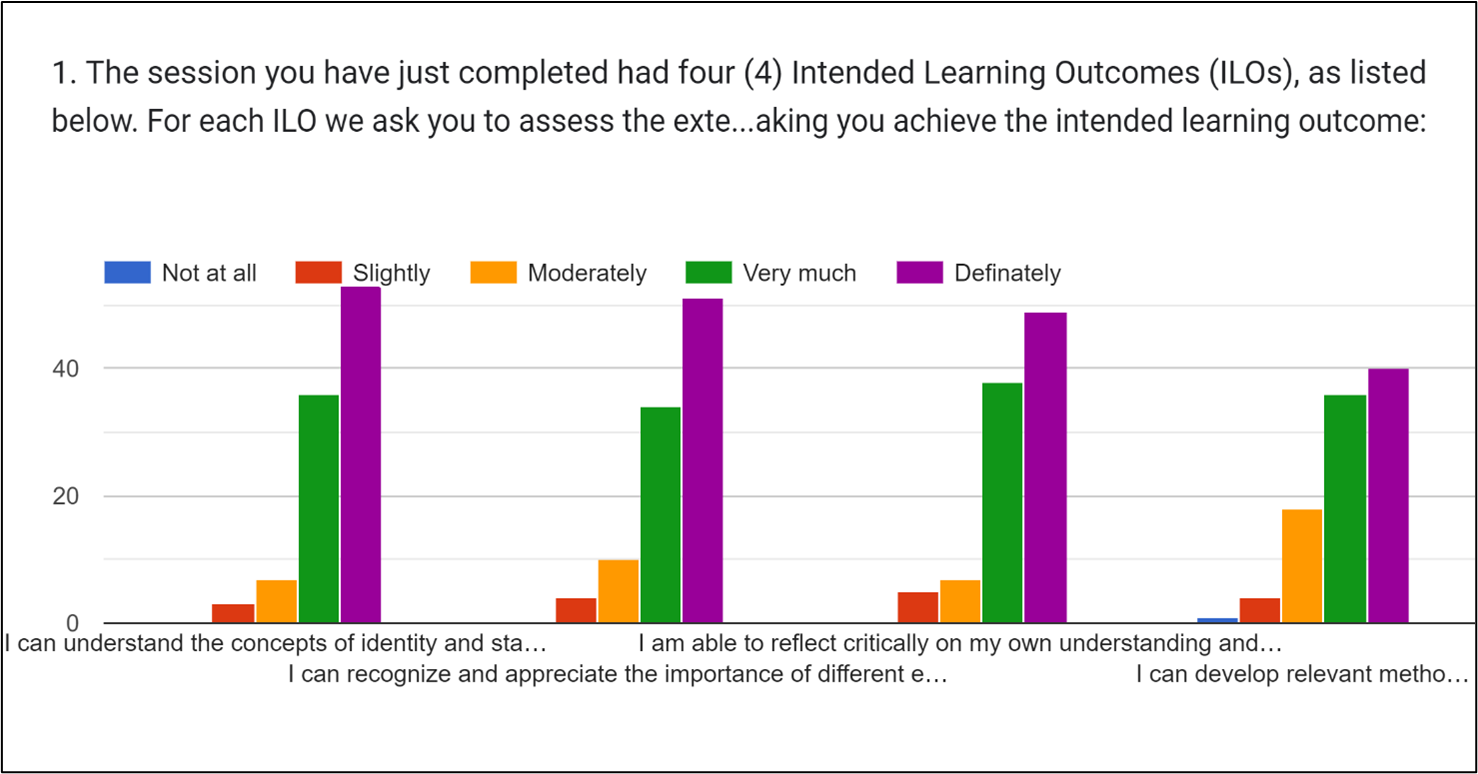

The second sub-assessment of the Training Programme’s individual sessions was based on the following instruction:

- Looking back, and looking at the session description, do you find that the topics, teaching contents and teaching material of the session were well chosen as means for achieving the Intended Learning Outcomes?

- Looking back, and looking at the session description, do you find that all assignments of the session were pedagogically meaningful?

- Looking back, and looking at the session description, do you find that assignment instructions were easy to follow?

- Looking back, and looking at the session description, do you find that all timeslots for assignments appropriate, neither too much time, nor too little per assignment

- Looking back, and looking at the session description, did you experience the session’s workshop activities as inspiring and learning enhancing?

Responses were delivered in five-point Likert scale fashion with the added option to do comments on specific problems. Below, we once more show two examples, one with low-end assessment results (figure 6), one with high-end results (figure 7).

Figure 6: One sub-assessment drawn from session 1

Figure 7: One sub-assessment drawn from session 6c

In attachment 6 all teacher students’ assessment results are provided. It is to be noted that these assessments were not only intended to supply summative, but also formative information. This follows from the fact that Training Programme implementation was organized with the intention of pilot testing the teaching material applied. Many details from attachment 6 will be scrutinized by the STEP UP-DC team with a view to improving session details. In this sense assessments results are useful.

* Patton, M Q. (2008). Utilization-Focused Evaluation (4th ed.), Sage.

As seen from a summative perspective, we also find the results satisfactory. The two lowest Likert-scale positions are not used very often. Differentiating between the given quality parameters tested, it seems that time allotment was the one that caused most problems.

Summing up

Two sets of assessment results have been presented. Both are based on teacher students’ experiences while participating in the STEP UP-DC Training Programme.

One set aims at uncovering the RFCDC-related related global learning impact on teacher students. Respondents describe the extent to which they, after Programme completion, see themselves as having become, through their participation, more capable of developing and nurturing RFCDC-based competence in a classroom setting or elsewhere. With regard to 32 out of 39 competence items respondents report significant positive changes. With regard to seven competence items less significant changes registered – partly reflecting the fact that respondents saw themselves as already possessing these competences when starting the Training Programme.

The other set of assessment results reflect students’ educational value judgements concerning the Training Programme’s singular sessions. These results may, in formative fashion, lead to Programme adjustments. Yet, as a whole, the results as they are add up to a positive Programme assessmernt.

Long term evaluation of the STEP UP-DC Training Programme should include assessment of STEP UP-DC students’ teaching performance after graduation. That is beyond the project’s reach. In the project’s short term perspective experienced mentors’ assessment of mentored students teaching performance during practicum is the best measurement of the project’s real-world effect that may be had.

As was the case with Teacher student questionnaires, mentor-directed questionnaires provide data both of a quantitative and a qualitative kind. Both sorts of data are discussed below.

A total of 28 practicum mentors participated in the project, 11 from UNic, 15 from NKUA and 2 from UoTh. Twenty-six mentor questionnaires have been returned.

Assessment results stemming from mentors

Mentors were asked to do two sorts of assessment of their students’ teaching performance.

- A comparison of CD-students with non-CD students

- An assessment of the CD-students cd-related competences ‘as such’

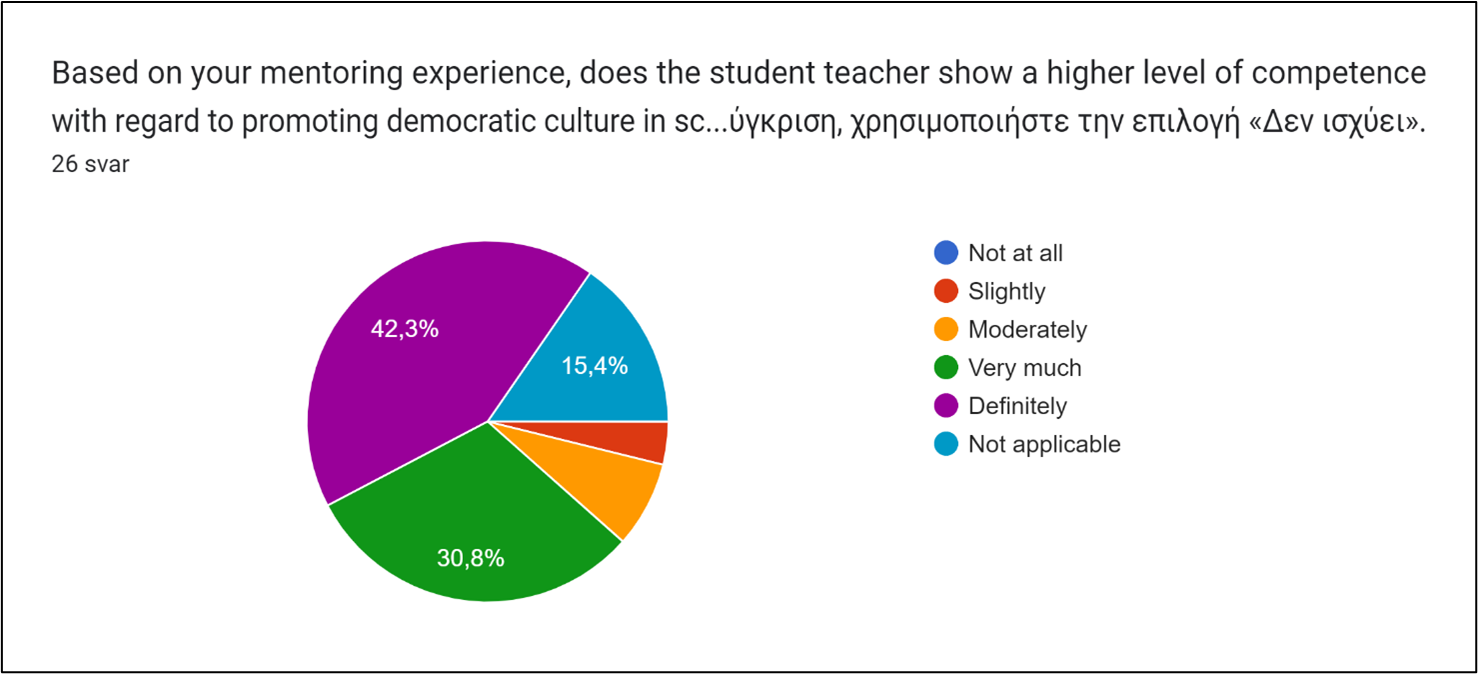

A comparison of CD-students with non-CD students

The following question was used:

Based on your mentoring experience, does the student teacher show a higher level of competence with regard to promoting democratic culture in school education than student teachers who have not participated in the STEP UP-DC project? – In case you lack experience to make such a comparison, please use the option ‘Not applicable’.

Mentors’ responses ran like this; cf. figure 8: For four among the 26 respondents the question’s content was Not applicable. Among the 22 respondents left, 19 find that their CD student differ ‘definitely’ or ‘very much’, and in a positive direction. Two respondents find the difference between the two students ‘moderate’. One assesses the difference as only ‘slight’.

Figure 8: Mentors’ quality assessment of STEP UP-DC students compared to ‘normal’ students

These results make it clear that, generally speaking, mentors perceive students who have participated in the STEP UP-CD module as having attained CDC-related teaching competences to a high degree.

Assessment of the CD-students CD-related competences ‘as such’

Mentors were asked to assess the student’s teaching performance by responding, in Likert scale fashion, to seven questions, formulated in third-person format. Those same seven question, but now in first-person format, were posed to students, as part of their response to the post-questionnaire. This procedure allowed us 1) to add nuances to the just described comparison between CD- / non-CD-students; 2) to compare mentors’ assessment of their students with students’ self-assessment; 3) to hand over to students and mentors a tool which might facilitate their mutual sharing of experiences at the completion of the practicum period.

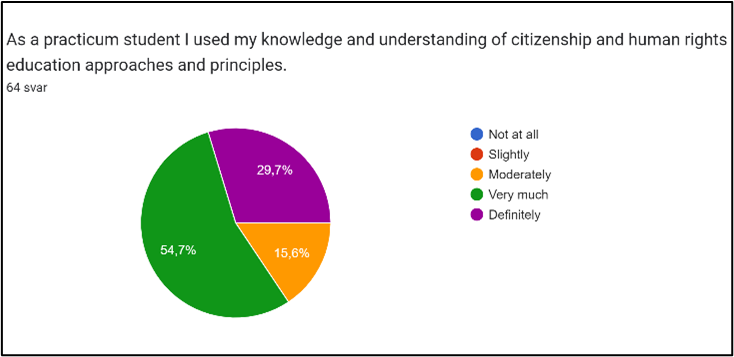

The representations of mentors’ and students’ responses to the seven questions show that, generally speaking, mentors and students share the opinion that students’ teaching performance shows very good qualities according to CD-based quality criteria (see below). Most prominently this is the case with regard to the following 5 questions

- Teacher student asks questions in class; see figure 9

- Teacher student shows knowledge and understanding of citizenship and human rights education approaches and principles

- Teacher student finds ways to carry out projects, do small experiments and gain practical teaching experience

- Teacher student critically reflects on his/her own teaching practice

- Teacher student uses interactive and participatory methods as part of teaching practice

Figure 9: Mentor and teacher students share positive assessment of students’ teaching performance

Ass for the following two questions quality assessment is more moderate

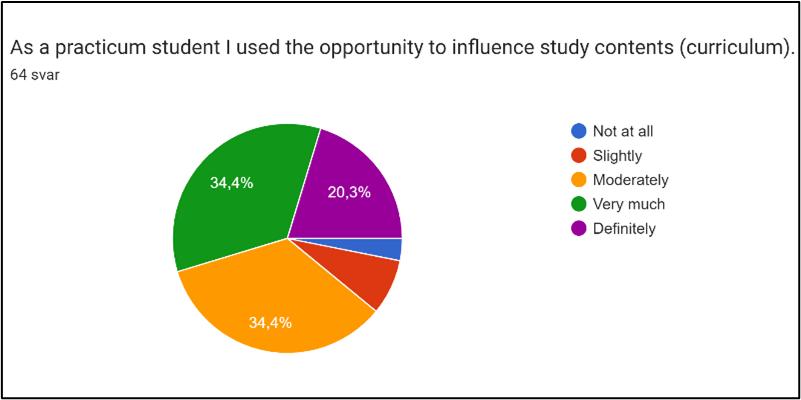

- Teacher student uses the opportunity to influence study contents; see figure 10

- Teacher student takes part in discussions on controversial issues

Figure 10: Mentor and teacher students share moderate assessment of students’ teaching performance

Roughly speaking, greatest agreement between mentors’ and students’ assessments are found in these three questions.

- Teacher student shows knowledge and understanding of citizenship and human rights education approaches and principles; see figure 11

- Teacher student critically reflects on his/her own teaching practice

- Teacher student asks questions in class

Figure 11: Mentor and teacher students share positive assessment of students’ teaching performance

In the following four questions mentors’ assessment is a bit less positive than students’

- Teacher student uses interactive and participatory methods as part of teaching practice; see figure 12

- Teacher student finds ways to carry out projects, do small experiments and gain practical teaching experience

- Teacher student takes part in discussions on controversial issues

- Teacher student uses the opportunity to influence study contents

Figure 12: Mentors assess teacher students’ teaching less positively than students

Did mentors gain professionally form their project participation?

Responsibility for first designing and then pilot testing the Training Programme rested with the STEP UP-DC core team members. This group found that, “professionally speaking, project participation has been for them an extremely rewarding experience”. Such sentiments are noteworthy, as far as the future expanse of the project within school communities is concerned. As measured in time, practicum mentors’ professional project contact was more modest, yet, evaluatively speaking, of high import. They were to function as critical-supportive eyewitnesses of the teacher students. We have seen that, generally speaking, they showed much acclaim for students’ learning-based teaching performance. Did they themselves also draw professional learning from their mentoring work? Information on this issue was collected through the following two questions.

First question:

Has mentoring inspired you to use any teaching method or technique that student teacher used? If yes, please describe

Eleven mentors (42%) indicate that they are not going to include methods used by teacher students in their own teaching practice. Three (12%) respond with a ‘qualified Yes’, such as “The techniques were good, but I knew them already, so they were not new for me”. Answers from twelve mentors 46%) range from ‘mildly positive’, e.g.: “You always try to get from students. I did not get something in particular, but they were quite positive” – to ‘very positive’, e.g.: 1) “Yes, I ask her to give me some of the material she used in the class;” 2) “I used the lesson plans made in collaboration with the student to other classes.”

Second question:

What have you learned from taking part in STEP UP-DC project?

Admittedly, the question is leading. It presupposes that doing mentoring for STEP UP-DC teacher students must have led to some kind of learning. The possibility of asking for a quantitative response, namely through the habitual five-point Likert Scale, was considered. The idea, however, was found to ascribe a non-existent unidimensional quality to the question theme and was therefore abandoned.

One out of 26 respondents, one (4%) refrains from being led by replying “Nothing new”. From the rest (96%) a wide variety of learning dimensions are touched upon. Five examples below move from ‘seemingly modest learning gains’ to ‘high impact learning’:

- I got in touch with the material of project

- It was a very good collaboration with the University and I hope to have next year such good students

- Innovative Teaching with an inclusive approach and a strong focus on promoting universal human rights and democratic culture. Ethos in Teaching for the 21st century TESOL practitioner!

- To try to include all my students in my lesson, to be open to new perspectives and views, to listen carefully, to express my opinion without being absolute and offensive.

- (heavily abridged quote) (…) I did the seminar in the university and the e-learning programme for pedagogy last year. I have changed the way of the evaluation and assessment. (…) I think now after two years that all teachers must know the corpus of the competences for democratic culture and especially how to use it in practice in schools with the students, in the classroom and with the other teachers and the principal. I think that we all should develop firstly our personal competences and then to teach them

Summing up

In section 3.4 two sets of assessment results have been presented. Both sets aim at uncovering the STEP UP-DC Training Programme’s CDC-related learning impact on participating Teacher students.

The first set shows that experienced mentors clearly view STEP UP-DC teacher students as demonstrating more CDC-based competences in their teaching activities than non-STEP UP-DC teacher students.

In the second set of assessment results teacher students as well mentors asses the teacher student’s teaching performance according to RFCDC-related quality indicators. This procedure was partly chosen as a means towards diminishing reliability risks that might otherwise become activated. Both practicum mentors and practicum teacher students might have personal reasons to either upgrade or downgrade their assessment judgements. Technically speaking, we dealt with this reliability issue through triangulation, i.e. by having both mentors and students do comparable assessments. In principle, we could have taken triangulation one step further by also asking the teacher student’s classroom learners to do assessments of the teacher’s performance. Under the given circumstances, however, we found such a step unrealistic.

Teacher students assessed the Training Programme’s singular sessions, one by one, with regard to their educational value. A similar assessment done by the Training Programme’s teachers would in principle be desirable. Yet, since the entire module, due to Corona restrictions, was delivered in an online format, the session-responsible teacher was not in a position to do experience-based assessment of the large majority of session components – but only to comment on scheduled workshops where direct, even if online teacher-student interaction took place.

Accordingly, teachers responsible for module sessions 1-6 were asked, after each completed session, to comment on the perceived education quality of the session’s workshop event based on these questions:

We ask you to fill in this questionnaire immediately after having completed a workshop, while the event is still fresh in your memory. For each of the areas mentioned below, we ask you, either to click the OK box or describe problematic aspects as you experienced them:

- Time allotment for whole workshop and for singular activities?

- Clarity of instructions?

- Usefulness of the materials?

- Relationship between activities and ILOs?

- Other comments

In the comparison between mentors’ / students’ assessment of CDC students’ performance the assessments are extremely positive. In four responses out of a total of 40, one assessor comments that time allotment for the scheduled activities seemed too constricted. No other critical issues were brought up. In a small-scale perspective these assessments are summative. In a larger-scale perspective they have a formative intent, in that the critical comments raised concerning time allotment may lead to future adjustments of the sessions in question.

At LBU an obligatory accreditation procedure precluded a full-scale implementation of the module’s seven sessions. The LBU partner’s pilot testing of the module was therefore organized like this:

- One focus group consisting of STEM trainees including maths, computer science, design and technology, and a teacher trainer was convened.

- Participants were introduced to the philosophy and aims of the STEP UP-DC Training Programme, module materials and assessment methods were demonstrated

- An in-depth feedback session was held and feedback was transcribed and analysed

- Further than that, teacher mentors specializing in maths were interviewed.

In condensed form, pilot testing gave these results:

- Teacher students on the one hand expressed keen interest towards inclusion of CDC-related teaching material in their curriculum.

- Yet, at the same time they also expressed awareness that non-STEM teacher students and those going into primary education would probably show interest in doing the full programme.

- Such viewpoints were further supported through interviews with mentors specializing in maths. It was said that, generally speaking, British educational policy prioritized instrumental, discipline-specific aspects of school teaching. The ensuing lack of direct focus on citizenship becomes a particular challenge for STEM specialists in so far as they struggle to connect with pupils’ social and societal contexts. In this way this pilot testing may be seen as a confirmation of results emerging from LBU’s efforts in the area of Needs Analysis.

On the STEP UP-DC digital platform certification is described like this:

The aim of the certification process is to connect the CDC and the teacher training to the growing demand of teachers for official certification of their knowledge and skills developing a certification process of teaching the CDC.

The STEP UP-DC team developed three categories of questions and activities for the online certification process according to the project’s indicators and the methodology which requires closed-ended questions:

- Written questions that are used for self-assessment and they are known to the participants (they are used in the quizzes of the training sessions).

- Written new and original questions that can evaluate the learning outcomes and are based on the educational material of the project.

- Video scenarios based on the educational material of the project and the interactive educational activities which the project developed.

Assessment process and findings

In November 2022 teacher students of Greek origin (partners NKUA and UoTh) have made themselves available for a pilot test of the certification material. The NKUA partner implemented the pilot test and observed no procedural problems. Participants made no queries. Everyone completed the test within the set time frame. As for assessment results, 74% achieved 80-100% (grade A), 22% achieved 60-79% (grade B) and 4% achieved 50-59% (grade C).

7 Quality indicators

The Guide for designing the module marked a turning point in the STEP UP-DC project’s development.

See here the Guide for designing the module

Its introductory text (page 2) runs like this:

This guide includes basic guidelines in order to translate our priorities and ideas for teaching student teachers the democratic culture into a module embedded in the universities’ curriculum and related to the practicum and implanted alternatively as a face-to-face or distance learning module.

(… ) The guide endeavour to support you throughout our obligations so that we can plan and structure the sessions and their activities focusing on what we aim the module to acquire, how we can make it interesting for our universities, and above all, how it can be considered as an engaging learning experience for the student teachers in the practicum.

From an evaluation perspective, the Guide is meant to warrant that the STEP UP-DC Training Programme accords with the requirements set forth in the application text:

The project aims to develop an innovative student teachers Training Program (TP) on teaching CDC based on transnational cooperation between partners with different national educational background and potential to contribute to it with different national experiences (page 57).

… develop a model for a trainings delivery using innovative and evidence-based socio-pedagogical methods that will be cost effective and will lead to a sustainable outcome after the completion of the funding (page 59).

(… ) The guide endeavour to support you throughout our obligations so that we can plan and structure the sessions and their activities focusing on what we aim the module to acquire, how we can make it interesting for our universities, and above all, how it can be considered as an engaging learning experience for the student teachers in the practicum.

Due to the Guide’s project-related significance, we shall here present a thematically ordered list of such features as make it merit the above descriptors. The list as a whole shall be seen as a set of quality indicators attaching to STEP UP-DC’s educational output.

Innovative

RFCDC (volume 3, chapter 4) emphasizes strongly the need for applying CDC-based teaching in the realm of teacher training. Such engagements may take many forms. Module building followed by module implementation is one of these.

In the Guide a generalized description of a CDC-based teaching module, ready for implementation, is presented. The module may be called innovative in that it is unique. One further, and definitely innovative specialty of the STEP UP-DC Guide, however, is that the module description is accompanied by an empty session structure (template) supplemented with a very detailed set of instructions on how to insert concrete knowledge and process items into this structure. The Guide, thus, serves as a pedagogical tool, not only for its enrolled students, but also for teachers who want to engage in session construction work within their own professional field. Such an engagement is in fact required by the very module, in that its session 7 has to be constructed by the teacher who is responsible for the teacher student’s practicum.

Validity with reference to STEP UP-DC’ value platform

As is today considered a must in all teaching programme building, the Guide emphasizes that the programme builder’s selection of teaching material must be based on decisions with regard to Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs): “What is the session’s hoped-for leaning impact on the student?”

As is natural, in teaching activities based on RFCDC, ILO’s also must reflect RFCDC values. This emphasis, however, is not only expressed in words, as a piece of good advice. Template instructions make it obligatory that all ILOs pertaining to a given section find their justification in one or more indicators mentioned in RFCDC volume 2. In principle, therefore, it can be expected that, insofar as a teaching session’s ILOs are in fact realized, CDC-related learning has in fact occurred. Whether, or to what extent, this ‘in principle-statement’ holds true can then be made subject to assessment.

Transferability

The Guide’s instructions provided have great linguistic clarity, but also put great demands on the professional person who shall implement them. More than ten STEP UP-DC team members have used the Guide for session building. All personal, interview-based assessment of the Guide’s usability have been positive.

Cost effective

The fact that all users of the Guide experienced it as an extremely helpful tool for session building makes it justified to, also, describe it as a cost effective tool.

Using innovative and evidence-based socio-pedagogical methods

As part of the general module description, pages 6-8 of the guide show a substantial list of website-based socio-pedagogical resources and publications on which the module is based and from which teaching session builders can draw educational inspiration.

Activity- and interaction-based teaching

In RFCDC, volume 3, page 29, it is stated that “(d)emocratic values, attitudes and skills cannot be acquired through formal teaching about democracy alone but need to be practiced”. This value-based attitude was also strongly emphasized by the EWC partner in its role as RFCDC expert.

The just mentioned RFCDC page also brings a list of five “Process-oriented methods and approaches” that may be used as educational vehicles for translating this value-based attitude into teaching practice. Given existing educational cultures at European universities, it cannot be taken for granted that future users of the STEP UP-DC Training Programme are, then and there, sufficiently acquainted with a process-oriented teaching style. It is, consequently, of great importance that the Guide 1) exemplifies democracy-enhancing workshop activities; 2) gives very detailed, precise instruction on how to design such activities.

Team supportive

It is a regrettable fact that educational institutions are often marked by a strongly individualistic culture. Each teacher manages his or her own classes. It becomes the task of students to integrate a fragmented learning field.

Such a culture sets limitations to what in RFCDC is called Whole school approach. In the Guide a model is presented for the way in which a group of teachers may collaborate as teacher session builders, each working within his/her own discipline, but at the same time sharing knowledge and mutually inspiring each other. Thereby establishing themselves as a CDC-team within the larger institutional context. The model is based on the actual teamwork that took place in the NKUA partner group.

5 Recommendations for future users

Establishing the value-based social framework

(T)he role of teacher education institutions (units) is truly complex and multifaceted: it is not only to train teachers to be able to make effective use of the CDC Framework in schools and other educational institutions (the “technical” side), but also to equip them with a set of competences necessary for living together as democratic citizens in diverse societies (the “substantial” side). Teachers who themselves act successfully in the everyday life of democratic and culturally diverse societies will best fulfil their role in the classroom (Council of Europe, vol. 3, 2018, p. 77):

Future users of the STEP UP-DC programme are recommended to be mindful of not only developing teaching competences, but also of developing social and CDC-related competences in the professional team responsible for programme design and implementation. Section 3.2 describe briefly such team development activities as were practiced in the STEP UP-DC project.

Adapting the programme to locally experienced needs

“ … curricula when implemented should reflect and be closely aligned to everyday, real-life issues.” Further than that, stakeholder participation in training programme design work accords in itself with RFCDC values (Council of Europe, vol. 3, 2018 p. 18); “All those involved – especially those who are the target of the curriculum – should have a voice and even take part in the decision making about its contents.” (Council of Europe, vol. 3, 2018 p. 17).

Future users of the STEP UP-DC programme are recommended to use the variety of tools and methods through which locally experienced needs may be uncovered: oral interview, written questionnaire, focus group interviews. Results from Needs’ Analysis exploration allow for adding special, locally relevant angles and foci to programme content thereby potentially adding to its learning impact;

Pilot testing draft versions of (selected) programme material

In the STEP UP-DC project two pilot testing events took place:

- In Spring semester 2021 Greek team members pilot tested selected programme components; Apart from supporting professional self-confidence with CDC pedagogy, this pilot testing also strengthened team spirit among participants; cf. Whole School approach.

- In Autumn and Spring semester 2021-22 the entire Training Programme was pilot tested in Cyprus (UniC) and Greece (NKUA, UoTh). As seen from an evaluative perspective, the purpose of this pilot testing was to gain information that, in formative fashion, could support programme adjustments which might be needed before the Training Programme could be placed as a finalized open educational resource on the project’s digital platform.

Future users of the STEP UP-DC format are not meant to view the platform’s Training Programme material as a ‘finalized’ package, ready for implementation; but rather as an inspirational source for further, locally contextualized design work. Pilot testing of relevantly adjusted programme material is therefore recommended. It is further recommended that teacher student participants contribute with assessment data.

Use the Guide for designing the module as design tool

RFCDC (vol. 3, chapter 1) proposes that its design principles and guidelines are used in a flexible, contextualized manner: “(I)t is not the function of the Framework to promote one particular curriculum approach.”

The curriculum approach chosen by the STEP UP-DC project has been to use CDC indicators (from RFCDC, vol. 2) as meticulously applied means for quality assurance. This approach is one important factor, both in making the project innovative and in giving it high validity in a RFCDC perspective. If started from scratch, such an approach is also extremely complex, and thus demanding, as far as professional time and energy is concerned. The above-mentioned Guide for designing the module, makes the approach accessible, even if still demanding.

Active mentor involvement

Practicum mentors were asked, not only to assess teacher students’ teaching proficiency, but also to comment on possible professional gains and practical inspiration they, themselves, might have had from collaborating with the students. Mentors’ qualitative responses indicate that the mentor-mentee relationship was one of mutual professional enrichment. In the light of CDC values, it is in itself gratifying that professional enrichment flows from mentee to mentor. As seen in a Whole School Approach perspective, mentors’ responses are also promising. Some explicitly express appreciation with regard to the university-school collaboration they have experienced. As a group, they may be expected to take on the role of positive CDC ambassadors, in their own school context and elsewhere.